Many years ago, our schools decided to rank individuals based on their test scores. I strongly believe that might be one of the reasons we have more teenagers than ever before taking medication that’s been prescribed for anxiety, stress and depression.

Due to the fact that our education system is relying more and more on standardised tests that compare students to one another as the dominant assessment instrument, our students are under increased pressure to perform. Moreover, there are studies that have been done that suggest regulated evaluation raises considerable anxiety amongst students, and that it seems to increase with their age and experience.

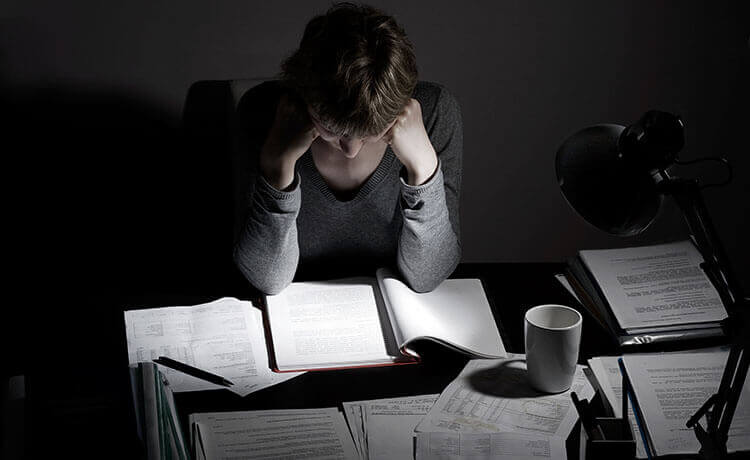

Stress and Teenage Students

Stress is the body’s natural response to any intense physical, emotional or mental demand. Even though we all have different tolerances, the response to a sentence like ‘there’s a final exam next week’ is likely to be similar to all of us. We will experience stress, that then triggers worrying and a lack of concentration.

In the brain, stress is processed in the prefrontal cortex, which is our cognitive function. Another area of the brain that is affected when we’re asked to process extreme stress that turns into fear and anxiety is the amygdala. This resides in the limbic system part of your brain that includes the hippocampus.

In teenagers and adolescents, the prefrontal cortex is not fully formed and the amygdala part of the brain is already quite overloaded processing other emotions that come with hormonal change and navigating the world on our own – venturing, as we tend to do at this age, into the community without our parents constantly there to prepare and support us.

In a nutshell, stress hurts students and their performance in the classroom. While there would be many adults – some experts and professionals in health, mental health and parenting – who will tell you that our young people need to learn to cope with stress, what neuroscience is telling us about the brain paints a very different picture.

The teenage brain has a lot to be coping with just dealing with life as a teenager. Today’s teenagers are exposed to too much, much more – like the constant stimuli of the internet, TV and social media. Their brains get very little ‘down time’ and we have to ask ourselves whether or not added stress in the classroom is really worth it. Are we damaging our kids’ brains, setting them up for an inability to cope with pressure long before the other – just as difficult to deal with – pressures of adult life (forging careers, financial commitments, raising children)?

Wouldn’t we be wiser to let their brains develop at a more measured pace, without all of the extra ‘mental activity’ and certainly without the pressures of having to perform day-in-day-out at school to be considered ‘successful’?

Dreading Those Psychometric Tests

I’ve spent my life working in corporations. I’ve read the results of and undergone many psychometric tests myself, so that the organisation I’m working with can see how I might handle myself in a stressful situation.

But… what if you are just not ‘wired’ that way? What if you can actually be composed in a real life stressful situation as it unfolds in front of you, but the stress of a ticking clock and time limit to ‘solve’ a theoretical scenario gives you a complete meltdown?

Adults are better at coping, but for teenagers, it can result in extreme rebellious behaviour, refusing to participate, taking days off schools or challenging the teacher.

And then, we have another generation of school leavers who are taught to believe that a number on a piece of paper is a measure of their contribution or their ‘worth’ and they won’t ‘fit in’ unless the score is good enough. Consequently, the scores become the basis for all sorts of comparative social judgments, completely bypassing the fact that schooling should really be about encouraging us to open our minds, to learn and to enjoy the process.

Mind Gone Completely Blank

Many of you will have probably experienced the ‘mind gone blank’ scenario. Can’t remember a name or a date or where you left your car, or sometimes, in the middle of a conversation, what you were going to say next.

Our brains are complex machines – and one of their important functions is that they allow us to concentrate on the task at hand, while storing useful information in a sort of ‘temporary storage facility’ for later on. But, when we stress out, we get a brain freeze. We go completely blank. Ironically, this is kind of a protection mechanism for the command centre of the brain, but it’s not helpful when we’re in the middle of that exam, presentation or speech.

Your Amygdala Is Hijacking Your Brain

The way that this all plays out is like this. It starts with the amygdala, that almond shape set of neurons located deep in the brain. Here is where we process emotions such as shame, fear and failure. The amygdala is constantly monitoring our experiences, and when this part of the brain is activated, the prefrontal cortex, (responsible for such things as reasoning, thinking, attention, planning, decision-making, logical thinking and short-term memory, amongst other things) takes a hike. It has a little (well-deserved) rest.

But unfortunately, this can mean that we sort of lose the plot and get stuck on the worst. The emotional intensity amplifies and we lose the ability to get the prefrontal cortex to swing back into action.

The way to fix this is to just stop. Pause. Breathe.

Reflect and take a moment to assess what just happened. Ask yourself – what has just happened right now? This is the really clever part: By asking a question, you are engaging your prefrontal brain with a question… and it snaps back to attention and the amygdala begins to settle down.

This tool – asking yourself a question – is useful for a few situations. For example, when you get into the habit of probing your brain, with some practice you can build awareness to shift from a reactive to a proactive brain. Remember, your emotions are your guiding force, so tune into them often.

It’s almost impossible to have two emotional experiences at the same time. Think about it, can you go left and right at the same time? I don’t think so. Next time you find yourself in a stressful situation, find a person, an object or situation to shift your thinking (your attitude) and therefore shift your emotion (your behaviour). As a result, you will have a more positive response to the external stimulus or stress.

Change Your Brain with Meditation

We understand how stress inhibits our brain’s ability to learn. With prolonged stress, the brain repeats the same responses over and over, strengthening the neural pathways that control the stress and fear responses. In essence, the brain is learning to stay stressed. There is research now that explains how mindfulness and meditation will improve attention, focus, stress management and self-awareness in less than a month (with daily practice, of course). It doesn’t take a lifetime of repetition; your brain can change as quickly as 21 days.

Apart from meditation and the practice of mindfulness, there is another component: train your brain. Just like any other muscle, you need to work on it to build it. This is how you rewire your brain with determination, continual effort and pushing through perceived failures. The only way to master this kind of risk is individual coaching outside of the classroom environment, taking students away from the stress stimuli and into the comfort of their own home, at their own space, in their own time.

It’s our moral duty to help and equip our teenagers with the coping strategies, encouraging self-awareness and emotional awareness. They require strategies to think for themselves, not to be influenced by peers. Instead, they deserve to be leaders that shine bright, learning to focus on their internal world through the practice of mindfulness and meditation to create real, life-long change.